WHO BURNED

RICHMOND?

266 266

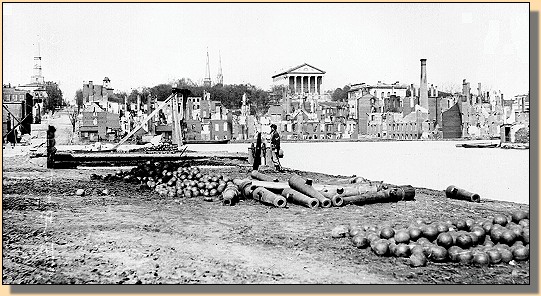

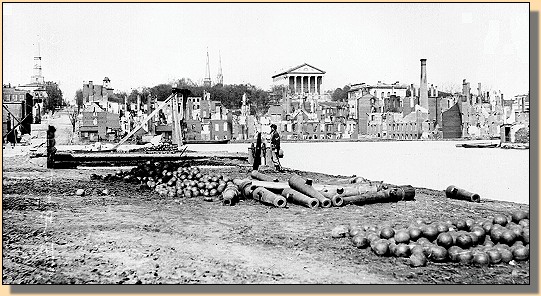

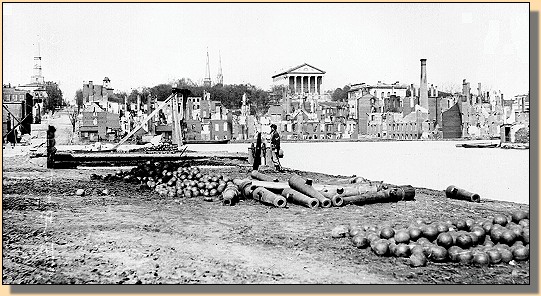

Ruins in front of the State Capitol, 1865.

(Richmond, Virginia)

Writers and interpreters of history, using basically the same source data,

sometimes come up with different conclusions concerning the same event. The

differences vary in importance, from minor, such as a soldier's opinion of an

event, to major, such as how many Union soldiers were killed in what period

of time at Cold Harbor or, as in this case, which actions resulted in the

business district of Richmond burning during the evacuation fire in April

1865.

The following illustrate this point

(Highlighting provided by the Editor.)

:

-

Nelson Lankford, author of Richmond Burning published by

Penguin Books, says, on page 107 of the paperback version of his

book,

"...Ewell (Confederate General.-Ed.) later laid responsibility

for the worst of the fires at the feet of the mob. He

swore

that they set fire to a large mill far from the tobacco warehouses fired

by his soldiers, and he further

alleged

that it was that burning mill, not the warehouses, that spread the

destruction. Certainly, in the predawn confusion,

some

of the looters

may

have set

some

fires. But Ewell convinced few people that the great fire had nothing to

do with his men or their deliberate demolition of the warehouses and

bridges through military orders passed down the chain of command...."

Perhaps the above statement is why Jonathan Yardley, of the The

Washington Post, says on the back cover of the paperback version,

"Unlike many of his predecessors, Lankford is able to see

without Lost Cause blinders or magnolia-suffused sentimentality."

Well let's see if we can continue

without Lost Cause blinders or magnolia-suffused sentimentality."

-

The National Archives, at

http:/www.archives.gov/research/civil-war/photos/,

says,

"...118. Silhouette of ruins of Haxall's mills, 1865, showing some of the

destruction

caused by a Confederate attempt to burn Richmond.

111-B-137...."

-

The Library of Congress, at http:/memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/apr02.shtml,

reports,

"...Richmond, meanwhile, burned, as fires set by fleeing Confederates

and looters"

raged out of control..."

-

The National Park Service, at

http:/www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hh/33/hh33s.htm, addresses

the burning of Richmond,

"...All semblance of law and order disappeared. When the guards at the

State penitentiary fled, the prisoners broke loose to roam the city at

will....The order had been given to burn all tobacco and cotton that could

not be removed by tossing flaming balls of tar into the warehouses along

the riverfront.

"...Mayor Mayo and the city council had appointed a committee in each ward

to see that all liquor was destroyed, and shortly after midnight they set

to work. Casks and barrels of the finest southern bourbons were rolled to

the curbs, the tops smashed open and left to drain.

"...The mobs swarmed and fought their way into the streets where the whiskey

flowed like water. Men...used...anything that would hold the...liquid. They

used rags on sticks dipped in whiskey for torches, and went howling through

the city in search of food and plunder like a pack of mad wolves, looting,

killing,

burning."

"...The blaze from the Shockhoe Warehouse at Thirteenth and Cary streets,

where 10,000 hogsheads of tobacco was put to the torch, flew skyward...The

flames quickly spread to the Franklin Paper Mills and the Gallego Flour

Mills.

"...A faint hot breeze began to stir from the southeast, scattering burning

embers through the streets and alleys and houses. Powder magazines and

arsenals let go with a whooshing boom. Thousands of bullets and shells tore

through buildings and ploughed up the streets.

"...Richmond was now one vast inferno of flame, noise, smoke, and trembling

earth. The roaring fire swept northwestward from the riverfront, hungrily

devouring the two railroad depots, all the banks, flour and paper mills, and

hotels, warehouses, stores, and houses by the hundreds.

"About dawn a large crowd gathered in front of the huge government

commissary at Fourteenth and Cary streets, on the eastern edge of the fire.

The doors were thrown open and the government clerks began an orderly

distribution of the supplies. Then the drunken mob joined the crowd.

"Barrels of hams, bacon, flour, molasses, sugar, coffee, and tea were rolled

into the streets or thrown from windows...When the building finally caught

fire from the whiskey torches, the mob swarmed into other sections of the

doomed city where the few remaining clothing, jewelry, and furniture stores

were ruthlessly looted and

burned."

A casket factory was broken into, the caskets

loaded with plunder and carried through the streets, and the fiendish rabble

roared on unchecked.

"As the drunken night reeled into morning the few remaining regiments of

General Kershaw's brigade, which had been guarding the lines east of

Richmond, galloped into the city on their way south to join Lee in his

retreat to Appomattox. They had to fight their way through the howling mob

to reach Mayo's Bridge. As the rearguard clattered over, Gen. M. W. Gary

shouted, "All over, good-bye; blow her to hell."

-

Charles B Dew, author of Ironmaker to the Confederacy published

by Library of Virginia, provides on Page 286 the following,

"...When the government began moving out of Richmond on the afternoon of

April 2, Anderson took added precautions to insure the safety of his plant

(Tredegar Iron Works -Ed.). Loyal members of the Tredegar Battalion

answered his call for aid, loaded their muskets, and took up positions

around the works. This action saved the Tredegar. Looting broke out as

Confederate troops tramped south across the James, and in the moonless early

morning hours of April 3 a rampaging mob seized control of the warehouse

district. Their ranks swollen by convicts who had broken loose en masse from

the nearby penitentiary,

looters spread the flames

originally put to government depots and tobacco storehouses.

Countermanding Gorgas' order not to destroy any ordnance facilities,

this motley crowd set fire to the Confederate arsenal,"

causing an explosion that shattered practically every window at the

Tredegar and sent shells crashing through the roofs of Anderson's buildings.

The arsonists then moved toward the nearby Tredegar plant to finish off

their night's handiwork. The resistance of Anderson and his men blunted

the thrust of the mob, however, and it broke and retreated back toward the

center of town."

In a footnote listing sources for the above, Dew says

"...Confederate troops did not attempt to burn Tredegar works, as several

of the above authors suggest"

So what is our opinion?

Obviously, the Confederates never intended to burn the city. We don't think

that even the Washington Post would take that position.

The mobs played a larger roll than current opinion wants to admit, in

spreading the fires.

As the fires spread, was their source the warehouse fires set by the

Confederates or the numerous other fires set by the mob? It appears more than

likely that both sources contributed to the destruction. But who knows which

fires were the source for which destruction?

And does it really matter now?

Yes it does. If we write or talk about the evacuation fires, we don't want to

be accused of having

"Lost Cause blinders and magnolia-suffused sentimentality,"

by a Washington Post employee.

Just our opinion,

Content Team

**

Bruce Catton addresses the "Lost Cause" in the book "Bruce Catton -

Reflections on the Civil War" edited by John Leekley, published by

Promontory Press.

On Pages 227-228 (hardback) Catton says, "The

essence of the legend of Lee and the dauntless Confederate soldiers was that

they suffered mightily in a great but lost cause. The point is that this very

phrase accepts the cause as having been lost. There was no hint in this legend

of biding one's time and waiting for a moment when there could be revenge.

This was the lost cause; something to be cherished, to be revered, to be the

outlet for emotions, but not to be the center of a new outbreak of violence.

In that sense, I think the legend of the lost cause has served the entire

country very well..."

Why the "Lost Cause" instills such dislike, approaching hatred, in the

Civil War elite, I have no idea. As an experiment, go on a History message

board and some where in your comments include the words "Lost Cause" (It does

not even have to be in context) and see what happens. Brace yourself, it will

not be pleasant. -Ed.

Return to Top

|

>

Opinions

> Burning Richmond

>

Opinions

> Burning Richmond

Notes

|

|

266

266

266

266